Inflation is one of the most commonly used terms when discussing the economy, especially in the context of the United States. If you follow financial news, you’ve likely heard about inflation rising or falling, but what exactly is it? Inflation refers to the rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising, and subsequently, purchasing power is falling. Simply put, when inflation occurs, each dollar buys fewer goods and services than it did before.

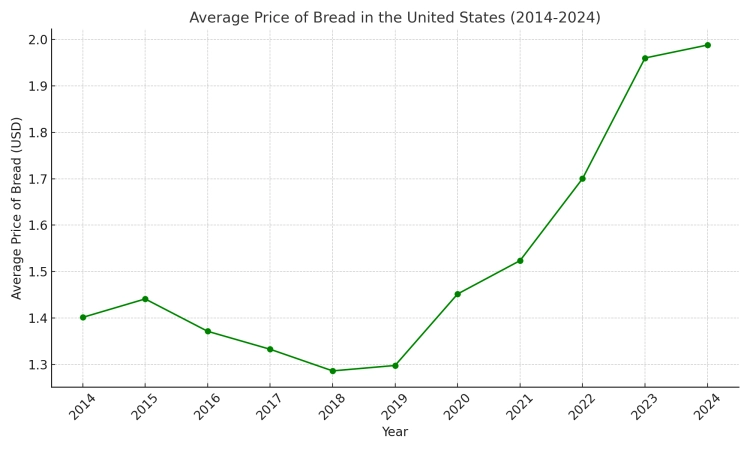

To grasp the concept of inflation more clearly, imagine you used to buy a loaf of bread for $2. If inflation rises, that same loaf of bread might cost $2.50 next year. In the short term, inflation affects the day-to-day purchasing power of individuals, but in the long term, it plays a crucial role in the overall health of the economy. This article will break down the causes, benefits, and downsides of inflation, particularly in the context of the U.S. economy.

Several factors contribute to inflation, but most fall into two broad categories: demand-pull inflation and cost-push inflation.

Demand-pull inflation occurs when consumer demand for goods and services increases faster than the supply. When more people want to buy products than there are products available, companies often raise prices. This increase in demand can happen for several reasons:

Cost-push inflation happens when the costs of production rise, pushing businesses to raise prices to maintain profit margins. This form of inflation is typically triggered by:

The Federal Reserve plays a key role in managing inflation through its monetary policy. When the Federal Reserve lowers interest rates, borrowing becomes cheaper, which can stimulate spending and investment. However, if this policy is too loose for too long, it can increase inflation. Conversely, if the Federal Reserve raises interest rates to cool down an overheated economy, it can help to lower inflation but may also slow economic growth.

Another cause is an increase in the money supply, which happens when the government prints more money or banks lend more. More money in circulation can lead to inflation because it devalues each unit of currency, making goods and services more expensive over time.

While inflation is often viewed as a negative phenomenon, it isn’t all bad. In fact, a moderate level of inflation is seen as necessary for a healthy economy. Here are some benefits of inflation:

When people expect prices to rise in the future, they are more likely to spend their money now rather than save it. This stimulates economic activity, as consumers purchase goods and services, and businesses invest in capital projects or expand their operations. A steady inflation rate encourages spending, which can drive economic growth.

Inflation can benefit borrowers, particularly those with long-term fixed-rate loans. As the value of money decreases over time, the real cost of debt also falls. For instance, if you owe $100,000 on a mortgage, and inflation is increasing, the amount you owe remains the same in nominal terms, but in real terms, it becomes easier to pay back as wages rise.

Governments also benefit from inflation in this way. The U.S. government borrows heavily to finance its activities, and inflation erodes the real value of its debt over time, making it easier to manage and pay off.

In an inflationary environment, wages tend to increase, especially if inflation is driven by a tight labor market where workers can demand higher pay. While this can lead to cost-push inflation, it also means that workers have more purchasing power, at least in nominal terms. This wage growth can improve living standards if it outpaces inflation.

Despite its benefits, inflation can also have significant drawbacks, especially when it rises too quickly or unpredictably.

The most obvious downside of inflation is its impact on purchasing power. As prices rise, consumers can buy less with the same amount of money. For those on fixed incomes, such as retirees, inflation can be particularly damaging. When Social Security or pension payments don’t keep pace with inflation, individuals find themselves struggling to afford basic necessities like food, housing, and healthcare.

High or unpredictable inflation creates uncertainty in the economy. Businesses may struggle to set prices or make long-term investment decisions if they don’t know how much costs will rise in the future. Similarly, consumers may become cautious about spending, fearing that their wages won’t keep up with inflation. This can lead to reduced economic activity and, in extreme cases, stagflation—a combination of stagnant economic growth and high inflation.

Inflation disproportionately affects savers because the value of money declines over time. For instance, if you saved $1,000 and inflation rises at 3% annually, that $1,000 will be worth less in the future. Without interest rates on savings accounts keeping pace with inflation, the real value of savings diminishes. This can discourage saving, which may reduce capital available for future investment.

While moderate inflation can be healthy, extreme inflation—known as hyperinflation—can devastate an economy. Hyperinflation happens when prices rise uncontrollably, often due to a collapse in confidence in a currency. In such scenarios, the currency becomes essentially worthless, leading to economic collapse. Historical examples of hyperinflation include Weimar Germany in the 1920s and Zimbabwe in the 2000s. While hyperinflation is rare in developed economies like the U.S., it remains a risk if inflation spirals out of control.

In the United States, inflation is commonly measured using two key indicators:

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is the most well-known measure of inflation. It tracks the average change over time in the prices paid by consumers for a basket of goods and services, such as food, housing, clothing, and medical care. The CPI gives a clear picture of how much everyday expenses are increasing.

The Producer Price Index (PPI) measures the average change in selling prices received by domestic producers for their output. While the CPI focuses on prices from the consumer’s perspective, the PPI looks at it from the perspective of producers. It’s a useful indicator for understanding inflationary pressures from the supply side of the economy.

The Federal Reserve (often referred to simply as the Fed) is tasked with keeping inflation under control while promoting maximum employment. The Fed aims for a long-term inflation target of around 2% per year, which is considered healthy for the U.S. economy.

To manage inflation, the Fed uses tools such as:

The primary tool the Fed uses is adjusting the federal funds rate—the interest rate at which banks borrow and lend to each other. When inflation is rising too quickly, the Fed may increase interest rates to make borrowing more expensive, which can slow down spending and investment. Conversely, when inflation is too low, the Fed may lower interest rates to encourage borrowing and spending.

Another tool is open market operations, where the Fed buys or sells government securities to influence the amount of money in the economy. By buying securities, the Fed injects money into the economy, potentially increasing inflation. Selling securities does the opposite, reducing the money supply and curbing inflation.

In times of economic crisis, such as during the 2008 financial crisis or the COVID-19 pandemic, the Fed has used quantitative easing (QE) to lower long-term interest rates and increase the money supply. While this can help stave off deflation or a deep recession, it also increases the risk of higher inflation if too much money is pumped into the economy.

In recent years, inflation has become one of the most pressing economic issues in the United States, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. A combination of factors caused inflation to spike to levels not seen in decades, leading to significant economic consequences and forcing policymakers to take aggressive action.

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered unprecedented supply chain disruptions, affecting everything from manufacturing to shipping. Lockdowns in key manufacturing regions, like China and Southeast Asia, meant factories were closed or operating at reduced capacity, limiting the production of essential goods. Additionally, restrictions on international shipping caused massive bottlenecks at ports, delaying the transportation of goods.

In the U.S., this meant that businesses faced difficulty getting the products they needed to meet consumer demand. For example, the automotive industry experienced a severe shortage of semiconductor chips, which are vital for modern cars. The shortage of these chips reduced the supply of new vehicles, driving up prices in both the new and used car markets. These supply chain issues were not limited to just cars but extended to electronics, household goods, and raw materials, contributing to widespread price increases.

While supply chains struggled to recover, consumer demand in the U.S. surged after the initial pandemic lockdowns were lifted. Pent-up demand from consumers, who had cut back on spending during the height of the pandemic, flooded the market as businesses reopened. People were eager to travel, dine out, purchase new goods, and generally return to normal life. This sudden increase in demand was supercharged by stimulus payments and other forms of government assistance, which put extra money in the hands of consumers.

This imbalance between high demand and constrained supply created a classic case of demand-pull inflation. When more people are chasing a limited number of goods, businesses respond by raising prices. For example, housing markets across the country saw prices soar as demand for homes outpaced the available supply, exacerbated by historically low mortgage rates.

The U.S. government played a significant role in the post-pandemic inflation spike through its fiscal response to the crisis. To avoid an economic collapse during the pandemic, the government introduced several rounds of fiscal stimulus, including direct payments to individuals, enhanced unemployment benefits, and various forms of support for businesses.

While these measures helped millions of Americans weather the pandemic’s worst economic effects, they also injected large amounts of money into the economy, contributing to higher demand. With consumers armed with more disposable income, they were able to spend more freely, further increasing pressure on already constrained supplies. While this helped drive a rapid recovery from the recession, it also fueled inflationary pressures.

The pandemic also caused disruptions in the labor market, which played a significant role in inflation. Many workers left the workforce during the pandemic due to health concerns, early retirement, or childcare responsibilities. This led to a labor shortage in key sectors like retail, hospitality, and manufacturing, forcing companies to raise wages to attract workers.

While higher wages can benefit workers, they also contribute to cost-push inflation. Businesses facing higher labor costs pass these increases on to consumers by raising prices for goods and services. For instance, restaurants raised menu prices to cover the increased costs of wages and raw materials, while retail companies did the same to account for rising shipping and production expenses.

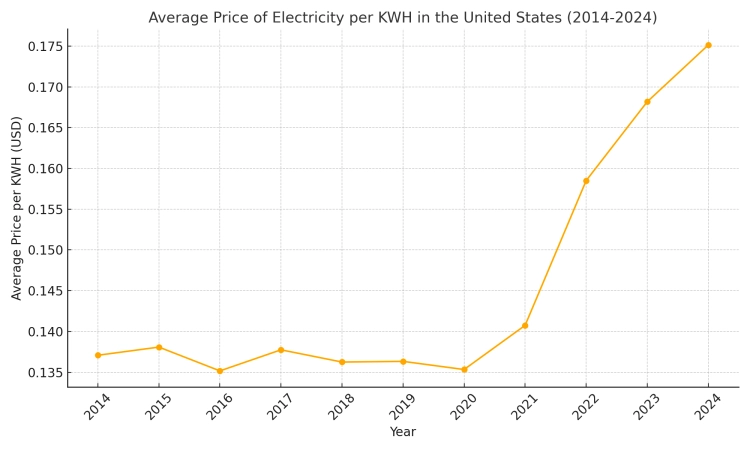

Energy prices, particularly for oil and natural gas, have been another major contributor to inflation. As global demand for energy surged post-pandemic, supply struggled to keep pace. The production of oil and natural gas had been reduced during the pandemic as demand dropped, but when the world economy began to recover, energy producers were slow to ramp up production. This led to significant price increases.

For example, oil prices shot up, reaching levels not seen since the early 2010s. This had a cascading effect across the economy. Higher energy costs mean higher transportation and shipping costs, which impact the price of goods across all industries. When companies have to pay more for fuel, those costs are often passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices for everyday goods, from groceries to electronics.

The U.S. Federal Reserve is responsible for managing inflation through its monetary policy. For much of the 2010s and into the pandemic, the Fed kept interest rates at historically low levels to encourage borrowing and stimulate economic activity. While this helped support the economy during tough times, it also made borrowing cheaper, fueling more consumer spending and business investment.

By 2022, inflation had reached a 40-year high, prompting the Federal Reserve to take aggressive steps to bring it under control. The Fed began raising interest rates in rapid succession, making borrowing more expensive. Higher interest rates aim to cool demand by discouraging consumers and businesses from taking out loans for big purchases, like homes and cars. However, the challenge is striking a balance—raising rates too quickly could slow the economy too much, potentially leading to a recession, while not acting fast enough risks allowing inflation to spiral further out of control.

Finally, inflation in the U.S. has been influenced by global factors. Disruptions in international trade, natural disasters, and geopolitical tensions, such as the war in Ukraine, have all had a hand in exacerbating inflationary pressures. For instance, the conflict in Ukraine caused energy prices to spike further due to disruptions in the supply of natural gas and oil, particularly in Europe, which had ripple effects on the global energy market. Additionally, rising food prices globally have contributed to inflation in the U.S., as the cost of importing certain goods has increased.

While inflation began to moderate in late 2022 and into 2023, it remains a central concern for policymakers, businesses, and consumers. The Federal Reserve’s balancing act between controlling inflation and avoiding a recession will likely define the U.S. economy for the coming years. As inflation stabilizes, it’s clear that the shocks from the pandemic, combined with global factors, have created long-lasting economic shifts that will shape the financial landscape for years to come.

Inflation is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that plays a crucial role in the health of the U.S. economy. While moderate inflation is necessary for economic growth, unchecked inflation can erode purchasing power, create uncertainty, and harm savers. By understanding the causes, benefits, and downsides of inflation, individuals and businesses can better navigate its impact.

For policymakers like the Federal Reserve, maintaining a balance between promoting economic growth and controlling inflation is key to ensuring long-term prosperity. As the U.S. continues to recover from recent economic shocks, inflation will remain a central focus, influencing everything from monetary policy to the cost of everyday goods and services.

By keeping an eye on inflation trends, understanding how it's measured, and recognizing its causes, we can all make more informed financial decisions.