In the heart of the Appalachian Mountains, deep in the coal-rich valleys of West Virginia, a tempest was brewing. It was the summer of 1921, and tensions were at a boiling point between the coal miners and their powerful, exploitative employers. For years, the miners had endured brutal working conditions, low pay, and a near-feudal system where coal operators reigned supreme. Living in company towns, where wages were paid in company scrip instead of cash and every aspect of their lives—housing, food, even healthcare—was controlled by the mine owners, the miners were virtual prisoners in their own communities.

The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) had been fighting tooth and nail to unionize these workers, facing fierce resistance from both the companies and the local law enforcement. The conflict would culminate in a massive armed uprising: The Battle of Blair Mountain.

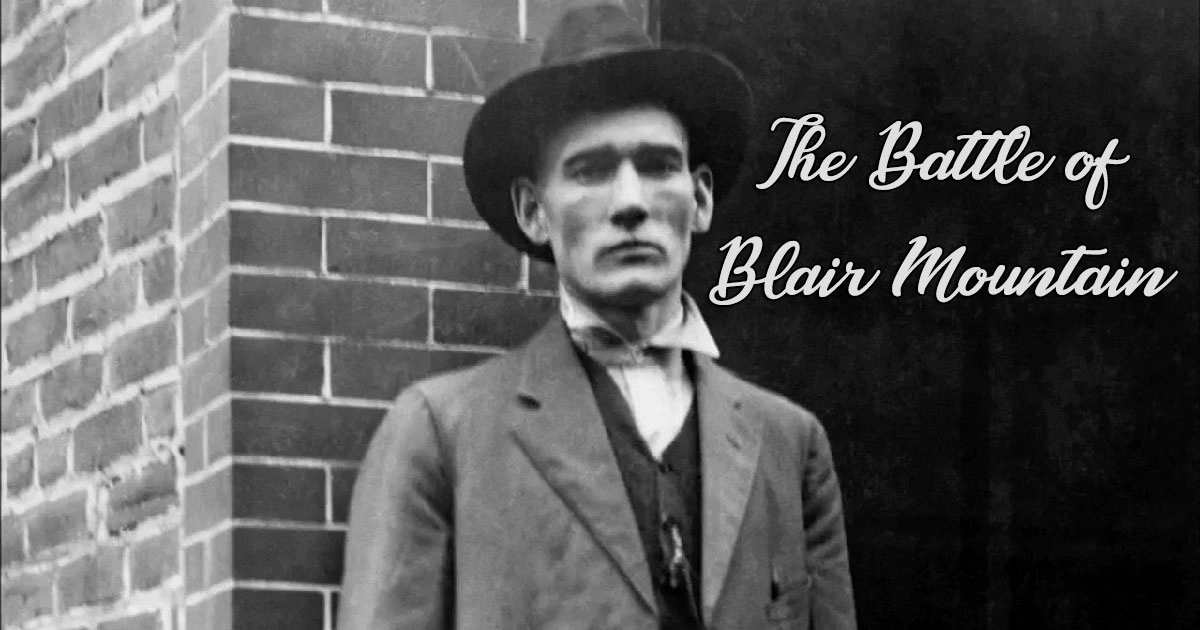

The miners’ demands for unionization were simple: fair pay, safe working conditions, and the right to have a voice. But every effort was met with harsh retaliation. In some parts of West Virginia, union organizers were shot at, beaten, and thrown out of their homes. One of the most vocal advocates for the miners was Sid Hatfield, a sheriff in the town of Matewan, who stood against the Baldwin-Felts agents—hired guns brought in to enforce company rules.

When Sid Hatfield was assassinated in broad daylight on the courthouse steps in August 1921, it was the final straw. The murder of a man who had become a hero and symbol of resistance to the miners galvanized them into action. Over 10,000 miners, many of them armed with hunting rifles and shotguns, began a march towards Logan County, West Virginia. Their goal was to confront the coal operators’ stronghold and demand justice.

Imagine an army of 10,000 men clad in overalls and work boots, their faces darkened with coal dust, marching through the winding roads of the Appalachian Mountains. They weren’t soldiers; they were fathers, sons, and brothers—all hardened by the relentless grind of mine work. Armed to the teeth and wearing red bandanas around their necks (earning them the nickname "Redneck Army"), these miners weren’t afraid. They were desperate.

Their destination was Blair Mountain, where a force of around 3,000 men—comprised of local lawmen and the coal company’s private army—stood waiting. The coal operators had dug in, fortifying the mountain with trenches and machine gun nests. It was a bizarre scene: a mountain turned battlefield, where fellow Americans would soon be fighting one another.

On August 25th, the first shots were fired. It was chaos. Men scrambled through dense woods, taking cover behind trees and rocks as bullets whizzed overhead. The miners, despite being outgunned and outnumbered, fought fiercely. Over the course of five days, both sides exchanged heavy fire, with reports of as many as one million rounds being fired.

The coal operators even took to the skies, using private planes to drop homemade bombs filled with nails and tear gas on the miners—a precursor to the aerial warfare tactics that would be seen decades later. Yet, despite the onslaught, the miners held their ground, advancing inch by inch up the mountain.

It’s hard to imagine today—Americans bombing Americans, with the government turning a blind eye to the abuse of workers. But in those moments, Blair Mountain was a war zone. And for those miners, it wasn’t just a fight for a better wage—it was a fight for dignity, for the right to be treated as human beings.

As the conflict dragged on, the coal operators called in reinforcements from the federal government. President Warren G. Harding, wary of a full-scale insurrection, sent in the U.S. Army. When troops arrived, the miners, realizing they could not stand against the might of the federal government, reluctantly laid down their arms.

Some miners were arrested, others went back to their homes, their spirits crushed but not defeated. In the aftermath, nearly 1,000 miners were indicted on charges ranging from treason to murder. Many faced lengthy prison sentences, and the UMWA’s efforts to unionize the region were set back by years.

In the end, the coal companies had won the battle, but the fight for labor rights was far from over. The Battle of Blair Mountain would become a symbol of the struggle for workers’ rights in America—a testament to the resilience and bravery of ordinary people standing up against extraordinary oppression.

Over time, the story of Blair Mountain faded into obscurity. Perhaps it’s because it challenges the romantic notion that the American Dream is accessible to all. Perhaps it’s because it’s uncomfortable to confront the lengths those in power will go to protect their interests. Or perhaps it’s simply because history is written by the victors, and the miners—despite their valor—lost this battle.

But in the grand scheme of things, the miners’ stand at Blair Mountain planted a seed. A decade later, during the New Deal era, workers’ rights saw monumental gains with laws like the National Labor Relations Act, which finally gave workers the right to organize and bargain collectively. So, while the miners of Blair Mountain may not have won the fight in 1921, they helped lay the groundwork for a better future.

Today, Blair Mountain still stands, scarred by history yet largely forgotten. Efforts to preserve it as a historic site have been met with resistance, as coal companies continue to eye its rich coal seams. But for those who know its story, Blair Mountain is more than just a mountain—it’s a monument to the indomitable spirit of the working class and a reminder of how far people will go to defend what they believe is right.

The Battle of Blair Mountain is a story that deserves to be told, not just for what it says about the past, but for what it teaches us about today. Even now, the echoes of that conflict can be heard in the ongoing struggles for fair wages and workers’ rights. The fight for justice, it seems, is one that never truly ends.