In the annals of military history, there are tales of epic battles, strategic genius, and heroic bravery. And then, there is the Great Emu War of 1932—a conflict so bizarre that it stands alone in its absurdity. This is the story of how Australia, a nation known for its rugged outback and resilient people, declared war on emus and lost.

The Great Depression of the late 1920s and early 1930s hit Australia hard. Unemployment soared, and the agricultural sector, particularly wheat farming, was in dire straits. To encourage wheat production, the government had promised subsidies to struggling farmers, but these subsidies never fully materialized, leaving farmers desperate and on the brink of ruin.

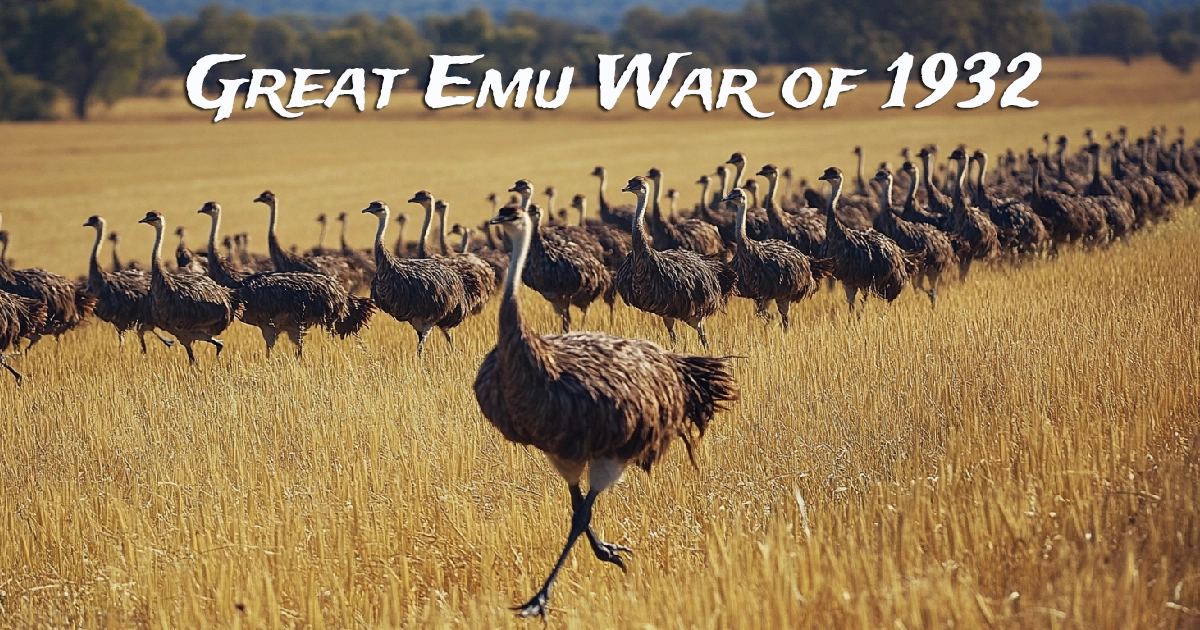

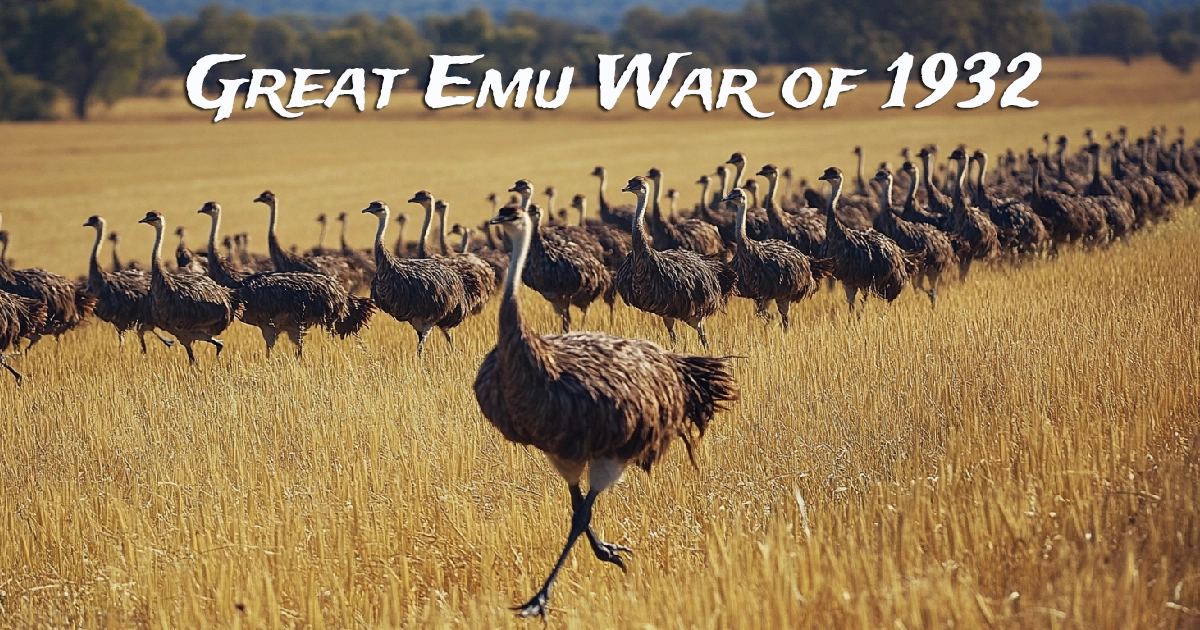

To make matters worse, the emus arrived. These large, flightless birds, native to Australia, were typically found in the interior regions. However, the emus, driven by the need for food and water, migrated en masse to the wheat-growing areas of Western Australia. By the end of 1932, an estimated 20,000 emus had descended upon the farmlands, causing widespread destruction. The emus trampled crops, ruined fences, and exacerbated the plight of the already struggling farmers.

The farmers, at their wits' end, sought help from the government. Their plea was simple: something had to be done about the emus. The birds were wreaking havoc, and conventional means of dealing with them—such as hunting—proved ineffective given their numbers and speed.

Enter Major G.P.W. Meredith of the Seventh Heavy Battery of the Royal Australian Artillery. The government, seeing an opportunity to assist the farmers and perhaps gain some positive press, agreed to send military aid. The plan was straightforward: soldiers armed with machine guns would be dispatched to the wheat fields to cull the emu population and restore order.

On paper, it seemed like an easy task. After all, how difficult could it be to defeat a bunch of birds?

On November 2, 1932, Major Meredith and his men, equipped with two Lewis machine guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition, arrived in Western Australia. The first attempt to engage the emus took place near the town of Campion, where approximately 50 emus were sighted. The soldiers set up their machine guns and opened fire.

But the emus were no ordinary adversaries. The birds, despite their size, were incredibly fast, reaching speeds of up to 50 km/h (about 31 mph). As the machine guns roared, the emus scattered, making it difficult for the soldiers to get clean shots. The emus seemed to move in a coordinated fashion, with one bird’s erratic movements leading the rest to safety. After the dust settled, only a handful of emus had been killed.

Undeterred, Major Meredith decided to try again a few days later. This time, they ambushed a group of over 1,000 emus near a dam. The soldiers anticipated a massacre, but the emus had other plans. The birds split into smaller groups and ran in all directions, making it impossible to mow them down efficiently. After expending a significant amount of ammunition, only about a dozen emus were killed.

As the days went on, the soldiers tried various tactics. They mounted one of the machine guns on a truck to chase the emus down, but the rough terrain and the birds' speed made this effort futile. The truck’s bumpy ride made accurate shooting impossible, and the soldiers eventually abandoned the idea.

By the end of the operation in December 1932, the numbers told a disappointing story. Of the 20,000 emus, only about 1,000 had been killed. Major Meredith and his men had fired over 9,000 rounds of ammunition, with a dismal success rate of about one emu per ten rounds. The emus had proven to be formidable opponents, much to the chagrin of the soldiers and the amusement of the public.

The emus, it seemed, had an uncanny ability to outmaneuver the military. They would appear in large flocks, tempting the soldiers into thinking they finally had them cornered. But as soon as the guns were trained on them, the birds would scatter in a flurry of feathers and dust, each group seeming to follow an invisible leader who guided them to safety. It wasn’t uncommon for soldiers to fire off several rounds at a single bird, only to watch it disappear into the bush, unharmed and unbothered.

In one particularly frustrating encounter, the soldiers set up an ambush near a watering hole, confident that they had found the perfect spot to catch a large group of emus unawares. They waited in silence, their fingers poised on the triggers. The emus approached, cautiously at first, then more boldly as they neared the water. The soldiers opened fire, but the emus reacted with startling speed. They bolted in every direction, zigzagging through the trees and bushes, their long legs propelling them faster than the soldiers could aim. The men watched in disbelief as the emus vanished into the landscape, leaving only a handful of casualties behind.

One soldier later recounted a particularly humiliating day when he and his comrades had chased a group of emus across a field. The birds, seemingly aware of the soldiers' presence, led them on a wild goose chase, darting in and out of the tall grass. The men were exhausted, their spirits dampened by the constant failure. As they finally gave up the pursuit, one emu, almost as if mocking them, stopped at the edge of the field and stared back at the soldiers before casually strolling into the brush. The soldiers could only watch, too tired to even raise their rifles.

Another soldier shared a story about a particularly crafty emu that they had nicknamed “The General.” This bird seemed to have a knack for outwitting the soldiers at every turn. Whenever they would set up an ambush, The General would somehow sense the danger and lead the flock away, avoiding the kill zone entirely. The soldiers grew to respect, if not outright fear, The General, whose survival seemed assured despite the military’s best efforts.

The press, both in Australia and abroad, caught wind of the so-called “Emu War” and had a field day. Headlines mocked the military’s inability to defeat the birds, and the operation was deemed a farce. One newspaper humorously suggested that the government award the emus military decorations for their prowess in battle. The Australian House of Representatives debated the issue, and after considerable embarrassment, the military was withdrawn from the operation. The farmers were left to deal with the emus on their own, and the government eventually resorted to offering bounties on the birds, which proved to be a more effective method of control.

Major Meredith, despite the failure of the campaign, reportedly had a sense of humor about the whole affair. He later remarked that the emus displayed excellent military tactics, calling them “cunning as a fox” and even comparing them to Zulu warriors in their ability to evade capture and slaughter. Meredith’s respect for the emus was echoed by many of the soldiers who had participated in the campaign. They had come to realize that the emus, far from being simple-minded creatures, were highly adaptable and resourceful—qualities that had allowed them to outsmart one of the most advanced military forces of the time.

In a post-war reflection, one of Meredith’s men commented, “We were outmaneuvered at every turn. You’d think we were hunting down a regiment of well-trained soldiers, not birds. But those emus, they had the better of us. I’ll never forget the look of defiance in their eyes. It was as if they knew they had won.”

The war highlights the challenges faced by Australian farmers during the Great Depression, as well as the often-overlooked impact of wildlife on agriculture. The emus were simply acting according to their instincts, searching for food and water in a time of scarcity. The clash between human agricultural interests and the natural behavior of the emus created a conflict that was as tragic as it was farcical.

Today, the Emu War is remembered with a mixture of humor and reverence. It has become a part of Australian folklore, a story told to remind people of the resilience of both the Australian landscape and its inhabitants—feathered or otherwise. The emus, for their part, continue to thrive in Australia, having earned their place as one of the country’s most iconic and enduring symbols.

In the end, the Great Emu War is a reminder that not all battles are won with firepower. Sometimes, the forces of nature are simply too strong, too swift, and too cunning to be easily overcome. And sometimes, those who seem the weakest—like a flock of flightless birds—can outlast even the most determined of foes.