The metric system has been embraced by nearly every nation across the globe, with the notable exceptions of the United States, Liberia, and Myanmar. These three countries continue to use variations of the British Imperial system for their measurements. This exploration delves into the reasons behind their resistance to change and poses the intriguing question, “Will they ever make the switch?”

The Imperial System has a rich and fascinating history that dates back several centuries. From the 1500s until 1826, the United Kingdom relied on the Winchester System for its standard measurements. This system was established and standardized under the rule of King Henry VII, and many of the measurements we use today can be traced back to him. For instance, there is a popular belief that the yard was based on the measurements of a monarch’s body.

In the later years of the 16th century, Queen Elizabeth I sought to update and refine the existing system. She introduced her own set of standards, which were based on an ancient collection of bronze weights. These weights, known as the Exchequer Standards, have been dated back to the time of King Edward III. The integration of the Exchequer Standards in the 16th century helped to further refine the system of weights and measures in use.

By 1826, the United Kingdom decided it was time for another change, and thus, the Imperial System was born. This new system was essentially a combination of the Winchester and Exchequer standards, creating a more unified approach to measurement. The Imperial System was widely used throughout the British Empire and its territories, becoming the primary system of weights and measures for many years.

However, as the world moved into the late 20th century, a shift began to take place. Most countries around the globe started to adopt the metric system, which offered a more straightforward and internationally recognized method of measurement. The simplicity of the metric system, with its base-10 structure, made it an attractive alternative to the Imperial System. Today, the Imperial System is still used in a few places, such as the United States, but the majority of the world has transitioned to metric for consistency and ease of use.

In 1832, the United States established its own system of weights and measures, known as United States customary units. These units were primarily based on the older English standards that were in use prior to England's adoption of the Imperial System in 1826. While U.S. customary units share some similarities with the Imperial System, they represent a distinct variation of the earlier English system, making them unique to the United States.

During the transition to U.S. customary units, certain names were modified, and slight variations in measurements were introduced. These adaptations resulted in a version of the system that was better suited to the needs and preferences of the United States. For instance, while both systems use units like inches and pounds, the values for certain measurements, such as gallons and tons, differ between U.S. customary and Imperial units.

Although U.S. customary units are rooted in the same historical standards as the Imperial System, the United States does not use the Imperial System in its entirety. Instead, it has maintained its own version, which has persisted over time despite the widespread global adoption of the metric system. As a result, U.S. customary units remain a separate and distinct system of measurement that continues to be used in everyday life and commerce across the United States.

The metric system, developed in France around 1799, emerged from the intellectual movement of the Age of Enlightenment. This period was marked by a push to replace traditional and often inconsistent systems of measurement with a more logical and universal standard. At the time, the older systems were seen as cumbersome and impractical, particularly for trade and scientific calculations. A new, simplified system was needed to promote consistency and efficiency.

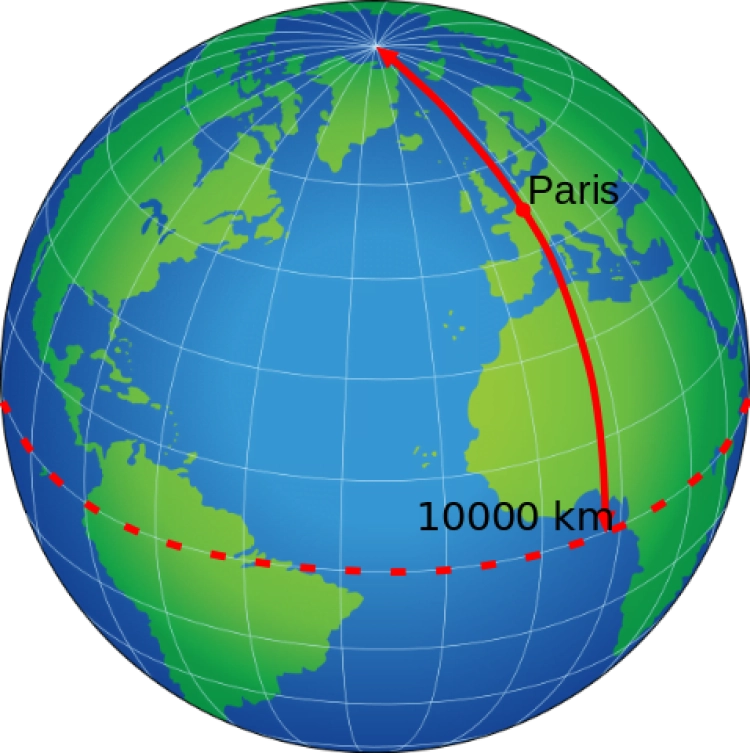

French scientists recognized that basing measurements on a constant reference, such as the size of the Earth, would be a rational and reliable approach. After seven years of careful surveying and calculations, they devised a system grounded in the Earth's dimensions. The meter, for example, was defined as one ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the equator. This approach created a standard that was not only universal but also rooted in natural constants.

Although the goal was to define one-quarter of the Earth's circumference as exactly 10,000 kilometers, the technology available at the time led to a slight miscalculation. Consequently, the actual circumference turned out to be 40,075 kilometers instead of the intended 40,000 kilometers. Despite this minor discrepancy, the metric system was still adopted and embraced due to its simplicity and ease of use.

Today, the metric system is widely accepted across the world for its base-10 structure, which simplifies calculations and conversions. Its adoption has greatly facilitated international trade, scientific research, and communication by providing a consistent and universally recognized system of measurement.

Once you divide the measurement down to meters or centimeters, the difference is negligible. It didn’t matter, and people eventually started to take hold of the new system. This change started slowly with adoption by a few surrounding European countries. But through colonialization, the system spread rapidly in the 1800s.

The basic unit of length in the metric system is the meter. It is the fundamental unit from which other metric units of length, such as centimeters, millimeters, and kilometers, are derived by applying a prefix that indicates a multiple or fraction of the base unit.

The metric system is a decimal-based system of measurement that uses standardized units for length, mass, and volume. It is based on the meter (for length), the kilogram (for mass), and the liter (for volume). The metric system employs a base-10 structure, making calculations and conversions simple and straightforward.

As of 2024, only three countries had not fully adopted the metric system: Liberia, Myanmar, and the United States. While Liberia has mostly converted and already conducts trade using the metric system, the U.S. and Myanmar appear to be the last remaining holdouts for the foreseeable future. However, the situation may be more nuanced than it seems.

Over the years, there have been several attempts in the U.S. to transition to the metric system. Many of these efforts have been blocked by Congress or met with opposition from anti-metric groups. In the United States, people are passionate about their measurements, and the resistance to change is strong.

A significant push to adopt the metric system took place in the 1970s and 1980s. On December 23, 1975, President Gerald Ford signed the Metric Conversion Act into law, creating a board tasked with overseeing America’s conversion to the metric system. However, in 1982, President Ronald Reagan disbanded the board, citing concerns about the cost of the conversion.

Despite the official stance against a complete transition to metric, the gradual adoption of metric measurements in various sectors of American society suggests that the U.S. may be moving in that direction, albeit slowly and subtly.

There is a fascinating anecdote often told about how pirates may have inadvertently prevented the United States from adopting the metric system. While it’s more of a "what if" scenario than a definitive explanation, the story of Joseph Dombey’s ill-fated journey provides an interesting lens through which we can view America’s complicated relationship with the metric system.

In 1796, Thomas Jefferson, who was the Secretary of State at the time, recognized the need for a standardized system of measurement in the young United States. With various systems in use, trade had become a complex and challenging endeavor. Aware of the new metric system being developed in France, Jefferson reached out to his contacts there to learn more about it. In response, the French sent scientist Joseph Dombey to America, carrying with him a 1-kilogram copper unit as a representation of the new system.

Unfortunately, Dombey’s journey took an unexpected turn when a storm blew his ship off course, leading him to the pirate-infested waters of the Caribbean. British privateers captured Dombey and his vessel, hoping to secure a ransom from France. Sadly, Dombey died while in their captivity.

The privateers auctioned off the contents of Dombey’s ship, and the copper kilogram piece eventually ended up in the possession of American surveyor Andrew Ellicott. The artifact remained within his family for generations until 1952 when Ellicott’s descendant, astronomer Andrew Ellicott Douglas, handed it over to the agency that would later become the National Institute of Standards and Technology. By then, however, it was too late for metric to gain a foothold in the United States.

Had the copper kilogram reached Thomas Jefferson, it is possible that the United States might have adopted metric. At that time, the country was struggling with a mishmash of different measurement systems, and the need for standardization was evident. Only three decades later, the U.S. ended up adopting the Imperial system, which means metric could have just as easily been chosen if circumstances had been different.

While this story is an interesting footnote in history, it’s important to remember that the actual reasons behind the U.S.'s decision to stick with customary units are more complex, involving cultural preferences, legislative choices, and economic considerations. The tale of Joseph Dombey’s ill-fated journey and the lost copper kilogram serves as a lighthearted reminder of how chance events and unforeseen circumstances can sometimes shape history in unexpected ways.