In 1994, a discovery deep within the El Sidrón cave system in northern Spain shook the world of archaeology: the remains of 13 Neanderthals who lived approximately 50,000 years ago. Forensic analysis of the bones uncovered a chilling truth; these Neanderthals had fallen victim to cannibalism. Skull fragments were found cracked open to access the nutrient-rich bone marrow inside, while evidence suggested that their tongues and even their brains had been consumed. The group consisted of a family unit, including seven adults, three teenagers, and three children, revealing a stark glimpse into a brutal prehistoric past.

The El Sidrón cave system, stretching an impressive 12,000 feet, features a central gallery approximately 600 feet long, which would have served as excellent shelter during prehistoric times. When the remains were first uncovered, they were mistakenly believed to belong to Spanish Civil War soldiers, as the cave had been used as a hideout by Republican forces. However, upon closer analysis, it became clear that these bones were far older, belonging not to 20th-century soldiers but to ancient Neanderthals.

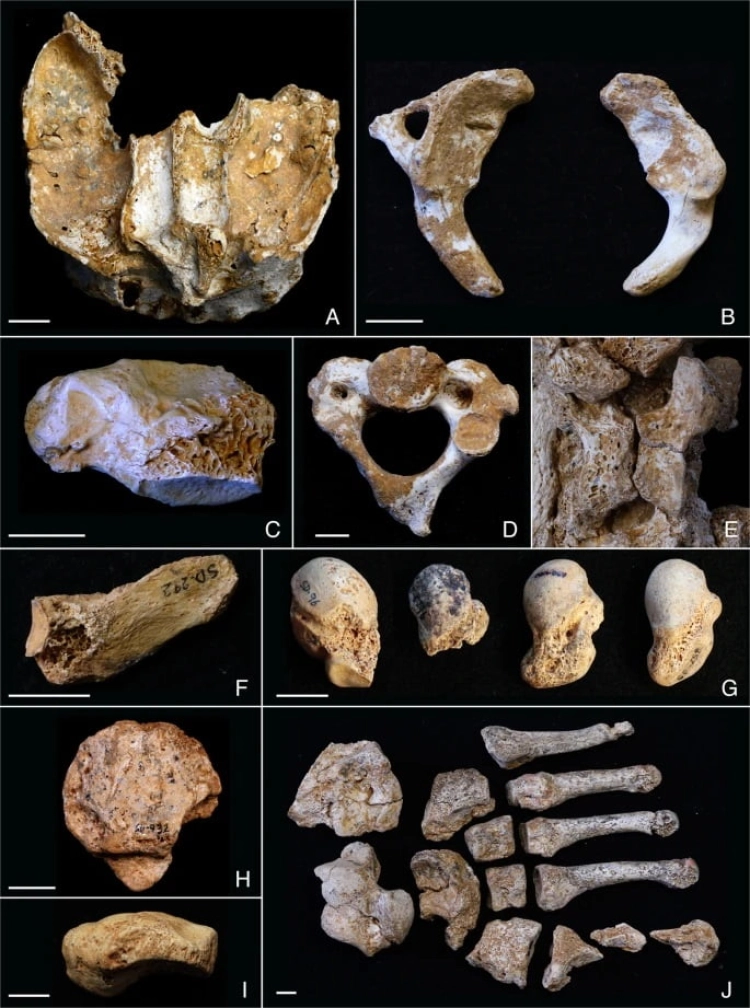

After determining that the bones were over 50,000 years old, a more detailed investigation began. From 2000 to 2013, researchers conducted extensive excavations, unearthing more than 2,500 bones concentrated in a single location within the cave known as the Ossuary Gallery, or the Tunnel of Bones.

The condition of these bones told a story of desperation and violence. Unusual wear patterns suggested a high degree of inbreeding, hinting that the local Neanderthal population was quite small and isolated. This finding sheds light on the potential reasons behind the eventual disappearance of Neanderthals from the fossil record around 40,000 years ago. Fragmented communities, with limited genetic diversity, may have suffered from a range of disorders and weaknesses, contributing to their decline and ultimate extinction.

Interestingly, the DNA of the group revealed that all the males were closely related, but the females had originated from outside the family unit. This implies that while the group was somewhat isolated, there were still interactions with other Neanderthal groups in the region. However, the pervasive signs of inbreeding across all individuals indicate that such connections were infrequent and likely dwindling.

The bones themselves bear the hallmarks of cannibalism: cut marks, pitting, and fractures consistent with the deliberate extraction of marrow. There were no signs of predation from large animals, no claw or bite marks, further supporting the conclusion that the damage was inflicted by other Neanderthals. The extent and manner of the bone breakage suggest a clear intent to access every bit of the nutrient-rich marrow, while evidence of malnutrition indicates these individuals were in dire circumstances. Their diet, primarily composed of plants and nuts with limited meat, lends credence to the theory that the cannibalism was driven by survival rather than ritualistic practices.

A Treasure Trove of Neanderthal Insights

The El Sidrón cave is not only one of the most significant archaeological sites in Spain but also a key location for understanding Neanderthal life. With over 2,500 bones unearthed, it boasts the most extensive collection of Neanderthal fossils in Europe. While the active excavation phase has concluded, ongoing studies continue to analyze the bones and artifacts discovered within the cave. Each new analysis adds another piece to the puzzle of Neanderthal behavior, social structure, and their eventual demise.

Among the bones, researchers have identified several congenital anomalies, including malformed vertebrae, ribs, and other skeletal abnormalities. These findings further support the theory that the Neanderthals of El Sidrón were part of a dwindling and inbred population, struggling to survive in an increasingly hostile environment.

The Importance of El Sidrón in Understanding Neanderthals

The El Sidrón cave system, nestled within the lush, rugged landscape of the Asturias region in northern Spain, offers more than just a glimpse into a prehistoric world; it serves as a poignant reminder of the vulnerability and resilience of an ancient human species. This remarkable site has become a cornerstone in Neanderthal research, providing clues that go beyond mere survival. The remains found at El Sidrón, along with the tools and artifacts left behind, have fundamentally shifted our understanding of these distant relatives, highlighting not only their adaptability but also the complex challenges they faced as a species on the brink of extinction.

A Window into Neanderthal Life

Unlike other Neanderthal sites, El Sidrón provides an exceptionally well-preserved snapshot of Neanderthal life approximately 50,000 years ago. The bones are remarkably complete and were found in anatomical positions, suggesting they were deposited rapidly, possibly due to a sudden natural event or burial. This pristine preservation has allowed researchers to conduct detailed analyses on everything from bone structure to genetic material, revealing much about Neanderthal biology and behavior.

One of the key findings from El Sidrón is the evidence of a family structure. The group consisted of at least three nuclear families, showing clear social bonds that went beyond simple survival. The DNA analysis of the bones has shown that the males were related, while the females came from different groups, suggesting a form of exogamy, or out-group marriage, to prevent genetic isolation. This finding indicates that, like modern humans, Neanderthals may have recognized the dangers of inbreeding and sought to mitigate it by bringing in females from other groups. Such social behavior hints at a level of organization and cultural sophistication that had previously been underestimated.

Stone Tools and Dietary Adaptations

Beyond the bones themselves, El Sidrón has yielded a wealth of stone tools, all meticulously crafted and used for a variety of tasks. These tools, made predominantly from flint, include scrapers, points, and cutting implements. Their sophisticated design suggests that Neanderthals were skilled artisans, fully capable of exploiting their environment to make tools that aided in hunting, processing food, and preparing hides. The tools at El Sidrón have provided critical insights into Neanderthal technology and their ability to adapt to different ecological niches.

Further analysis of residues on the tools and in the dental calculus (hardened plaque) of the Neanderthals has shed light on their dietary habits. It appears that they consumed a variety of plant-based foods, including nuts, seeds, and even medicinal herbs such as yarrow and chamomile. This challenges the old stereotype of Neanderthals as primarily meat-eaters and shows a more complex dietary strategy that involved gathering and possibly even the use of plants for medicinal purposes. Such a diet would have been essential for survival in the harsh environments they inhabited, where resources were often scarce.

Genetic Insights: The Role of Inbreeding and Genetic Disorders

One of the most groundbreaking revelations from El Sidrón has come from genetic analysis. The DNA extracted from the bones revealed that this group had a high degree of inbreeding, evident from the numerous congenital anomalies found in the skeletal remains. These included malformed vertebrae, fused bones, and other skeletal deformities that would have made daily life more challenging. Inbreeding within small, isolated populations likely led to a higher prevalence of genetic disorders, weakening the group’s overall fitness and ability to adapt to environmental changes.

This discovery has implications for understanding the broader decline of Neanderthal populations across Europe. It suggests that as Neanderthal communities became more fragmented and isolated, they increasingly resorted to breeding within the group, leading to a genetic bottleneck effect. The genetic weaknesses resulting from this inbreeding could have made them more susceptible to disease and less adaptable to changing climates, ultimately contributing to their extinction.

A Portrait of a Species at the Edge

While the bones and tools tell one part of the story, the setting of El Sidrón itself plays a role in the narrative. The cave’s hidden, maze-like passages would have provided shelter and protection from predators and harsh weather, making it an ideal living space. But it also suggests a life lived on the margins, away from more open landscapes where other, more prosperous groups might have thrived. The location of the site, far from any known Neanderthal settlement centers, implies that the El Sidrón group may have been part of a dwindling population, pushed into less desirable territories as competition for resources increased.

The evidence of cannibalism at El Sidrón adds another layer of complexity. Was it simply a matter of survival, a response to starvation during particularly harsh conditions? Or was it a ritualistic practice, perhaps reflecting a form of mourning or reverence for the dead? Whatever the reason, it serves as a stark reminder of the desperate conditions these Neanderthals faced. The cut marks and broken bones tell a tale of scarcity, hardship, and ultimately, the extinction of a group and, eventually, an entire species.

Research Continues

Although the active excavation at El Sidrón has concluded, the site continues to yield insights through ongoing research. Every new discovery, every bone and tool analyzed, adds to our understanding of Neanderthal behavior, biology, and social structure. As researchers continue to study the remains and artifacts, they hope to answer some of the lingering questions about how these people lived and died.

The El Sidrón cave is indicative of the complexity of Neanderthal life and the challenges they faced in a world that was rapidly changing. It shows us the fragility of small populations and the devastating impact of isolation and inbreeding. But more importantly, it humanizes the Neanderthals, revealing them not just as primitive beings but as a species capable of intricate social relationships, skilled craftsmanship, and adaptive strategies for survival, qualities that are hauntingly familiar to our own.

In this light, El Sidrón serves not only as a scientific treasure but as a somber reminder of a shared history, echoing through the dark chambers of the cave and into the present, where we continue to search for the threads that connect us to these lost relatives of our past.